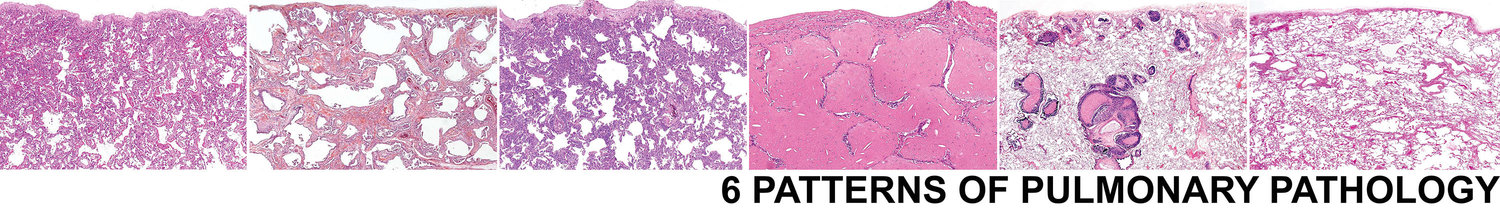

Pattern 2 Fibrosis

Basic Elements of the Pattern: Interstitial edema, alveolar space fibrin, neutrophils, reactive type 2 cells.

Key Modifiers: Temporal heterogeneity, uniform alveolar fibrosis, airway-centered scarring, isolated stellate scars, microscopic honeycombing,

Interstitial lung fibrosis is frequently accompanied by permanent and irreversible alteration of lung architecture. After Pattern 1 Acute Injury, fibrosis tends to carry great prognostic significance for the patient. It is essential that pathologists learn to recognize the different patterns of fibrosis that occur, as they derive from different mechanisms, carry different prognostic implications, and one day may influence targeted therapies. One of the hallmarks of such irreversible damage has been termed “honeycombing”, in reference to the large interconnected cystic spaces that can be seen on CT scans of the chest and in whole lung sections. Such “gross” or “macroscopic” honeycombing is often recapitulated at the microscopic level, where it is referred to as “microscopic honeycombing” (Fig CT Gross and micro panels).

The relative maturity of fibroblastic proliferation and collagen deposition can help separate forms of interstitial fibrosis as well. Immature fibroblastic tissue can be seen in organizing DAD and in the OP pattern; these last two conditions may be reversible to some extent. Interstitial pneumonias with any degree of fibrous proliferation have often been lumped together as “pulmonary fibrosis.” Such cases invariably represent a histologically diverse group and can be better classified into one of the three patterns presented earlier: organizing DAD, OP pattern, and interstitial fibrosis.4Biopsies of organizing diffuse alveolar damage, and diseases that show an OP pattern, may have an impressive and even massive fibroblastic proliferation. Nevertheless, many such patients recover without apparent deficit and do not develop progressive lung disease. On the other hand, the “mature” interstitial fibrosis and honeycomb lung remodeling that characterize IPF represent endpoints of a progressive disease process wherein deficits accumulate over time. Thus, the character of the fibrotic or fibroblastic proliferation is important prognostically, and all cases of “pulmonary fibrosis” are not the same.12 In light of these inherent prognostic differences, a general morphologic approach to diffuse lung fibrosis should include an assessment of the distribution and character of the fibrotic or fibroblastic reaction, the degree and extent of mature interstitial scarring, and the presence or absence of honeycomb remodeling.4,5 The following general patterns of fibrosis can be very helpful in separating categorizing fibrotic lung diseases.

2a. Temporal heterogeneity

Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) is the prototypic chronic interstitial pneumonia with “temporally heterogenous” interstitial fibrosis and honeycombing (both microscopic and macroscopic) .4,5,16,17Most patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have UIP on surgical lung biopsy.19 UIP is characterized by a histologic appearance in the biopsy specimen that includes zones of normal lung tissue adjacent to zones of advanced architectural remodeling. The latter is recognized by confluent and dense scarring of the alveolar parenchyma. Microscopic honeycombing occurs early in the process and consists of irregular cysts containing mucus, aggregated in dense fibrosis. For me microscopic honeycombing requires fibrosis on at least 3 sides of the aggregated cysts, a criterion that helps to avoid including foci of peribronchiolar metaplasia under this designation. Small discrete foci of active fibroplasia are always present in UIP, but they are not specific for UIP. These “fibroblastic foci” occur at the interface between dense scar and adjacent normal lung. These three key elements of UIP are frequently related to one another in the biopsy, as a transition from old disease (fibrosis) to normal lung occurs, with active “fibroblast foci” forming a leading edge between them (this is the concept underlying the term “temporal heterogeneity”—heterogenous in time, with yesterday’s lung destroyed by fibrosis, tomorrow’s lung waiting to be consumed, and fibroblast foci sitting at the interface (today). A peripheral acinar pattern can often be recognized in UIP,3,4 accompanied by relative centriacinar sparing. These findings help distinguish UIP from other lesions (see below) with interstitial fibrosis and honeycombing (Table 8).

The lesions listed in Table 8 may be associated with considerable variation in the patterns of scarring. For example, sarcoidosis can produce scarring along lymphatic routes, while hypersensitivity pneumonia, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis and aspiration can produce centriacinar scarring. In addition, many of the conditions listed may have concomitant features that point to a specific diagnosis, while the fibrosis itself may be nonspecific.

UIP is now the required histopathological pattern for a diagnosis of clinical “idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis”. DIP represents a distinct pathologic entity that has clinical, radiologic, and prognostic differences from UIP. The hypothesis that DIP represents an early (“cellular”) phase of UIP is untenable based on incidence alone. A more appealing notion is that some forms of NSIP (see below) represent early manifestations of UIP, or alternatively are poorly-sampled examples of UIP. Furthermore, a number of cases previously classified as DIP have been reclassified as “respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease” (RBILD), an interstitial lung disease of smokers that does not appear to progress to advanced fibrosis. The DIP pattern is discussed under pattern 4 Alveolar filling.

1b. Uniform alveolar wall fibrosis

The occurrence of “interstitial” fibrosis that tends to preserve alveolar structure (i.e. little confluence of scar) characterizes a fairly limited group of diffuse lung diseases, dominated by rheumatic diseases, chronic drug reactions, and some examples of chronic hypersensitivity. An idiopathic form (referred to as “fibrotic non-specific pneumonia” or “NSIP) was formally described by Katzenstein and Fiorelli in 1994 who reported on 64 patients whose lung biopsies showed cellular interstitial inflammatory changes that did not fit within the spectrum of diseases originally described in Liebow’s historical classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias.18 In their report, they coined the term “nonspecific interstitial/fibrosis (NSIP/F)” for the patterns identified, and openly recognized that these patterns likely represented a wide variety of inflammatory processes affecting the lung. These authors emphasized the temporally uniform appearance of the disease process; that is, the pathology seemed to reflect a single injury in time (i.e. lacking a spectrum ranging from new disease to old).

Perhaps the most important finding in the Katzenstein & Fiorelli study was that their population of patients had a morbidity and mortality rate significantly different from that expected for UIP. Only 5 of 48 patients with clinical follow-up died of progressive lung disease (11%), while 39 patients either recovered or were alive with stable lung disease. These mortality data contrast sharply with those of UIP, where reported mortality figures are more in the range of 90%, with median survival in the range of 3 years.21

1c. Airway-centered fibrosis

When scarring occurs around bronchioles the differential diagnosis is limited to inhalational and aspiration-associated injury, and rarely certain rheumatic conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis. In some biopsy samples the airway-centered nature of the process may be difficult to discern, especially when fibrosis is advanced and/or the biopsy is small. As airway-centered diseases progress they can overwhelm the lobule, leading to scar that is difficult to classify. When this occurs, the HRCT distribution may be helpful as UIP and the autoimmune diseases tend to involve the periphery and lower lung zones, while diffuse inhalational injuries tend to have a more mid and upper lung zone distribution (at least relatively early in the process). Conditions resulting in airway-centered scarring are presented in Table10.

1d. Isolated stellate scars

The late stages of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (a smoking-related diffuse lung disease) are characterized by the presence of stellate parenchymal scars. They are distinctive and typically have few or no residual Langerhans cells. We refer to these as “healed” lesions of LCH. They may be incidental when the biopsy is performed for localized disease (like carcinoma). When numerous, consider “smoking related lung disease” as the correct diagnosis and cause for reticulation on HRCT scans (often accompanied by emphysema).

1e. Microscopic honeycombing only

Many unrelated lung diseases can result in localized areas of complete structural remodeling with the formation of microscopic honeycomb cysts in fibrosis (e.g. local healed infection). Context is essential. If the patient is over 60 years of age and peripheral bibasilar fibrosis is present on HRCT, the correct diagnosis is nearly always UIP, although the UIP diagnosis today requires some normal preserved lung in the biopsy to establish “temporal heterogeneity”.